Variation and Selection: Human Food Crop Selection Creates an Engaging Storyline

Variation in traits among individuals in a population is such an important concept that it first appears in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)* in first grade, then recurs through middle and high school standards. Yet, if we follow the traditional biology path for teaching variation and natural selection, we miss valuable opportunities for learning about variation and selection in food systems.

Food systems directly affect all humans—past, present, and future. For this reason, we share in this article a variation on teaching natural selection that is situated in the context of Brassica vegetable domestication, a major food crop in cultures worldwide. With this approach, learning possibilities include:

- How environmental and genetic factors influence the growth and development of organisms

- How humans influence the inheritance of organisms, such as through plant breeding

- How scientists can use classification as a useful tool for understanding relatedness among organisms

- The cultural relevance of Brassica domestication worldwide

- Science practices associated with modeling plant breeding with Wisconsin Fast Plants®

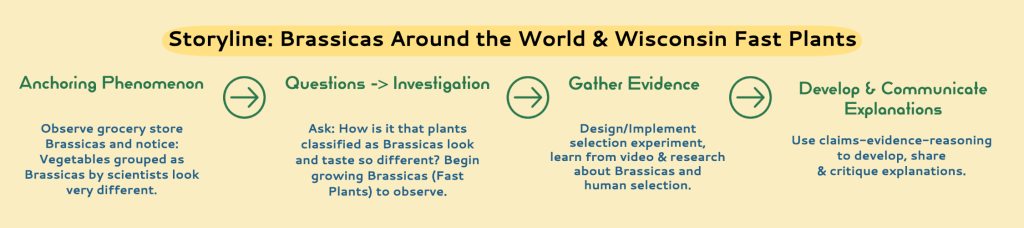

Here, we share an example of a storyline for teaching variation and selection through the lens of human selection for Brassicas along with several open-source resources for teaching with that focus. Included are links to:

- Planning and overview calendar for the plant breeding experiment

- Sequence timeline for implementing the plant breeding experiment (can be a student handout)

- A 10-minute, information-packed and interesting video titled Brassicas Around the World and Fast Plants, produced by the Wisconsin Fast Plants Program of UW-Madison (intended for use with middle or high school students)

Noticing Brassica Variation: An Easy, Produce Department Phenomenon!

Investigating Brassica variation can begin with common vegetables found at most any grocery store. Included in the genus are broccoli, cauliflower, turnips, and cabbage. Some students may be familiar with these vegetables from grocery stores or meals. Most importantly, all students can easily observe them firsthand if a selection of these easy-to-find vegetables are brought into class.

First, students share some wondering about these vegetables’ modified structures (e.g., roots, stems, flower buds) and recall what they can about having eaten any types. Then, students are told these vegetables have a common scientific classification as Brassicas. From there, it’s an easy path to guide students’ questions toward a natural phenomenon: Many of the vegetables that botanists classify as Brassicas look and taste very different.

Beginning a Brassica Selection Experiment with Wisconsin Fast Plants

Fast Plants serve as a relevant model organism in this storyline because they, too, are classified in the genus Brassica. Wisconsin Fast Plants is the common name for a special variety of Brassica rapa. Remarkably, Brassica rapa includes many different forms of vegetables like turnips, bok choy, and broccoli rabe. Further, we now know that this group of plants called Brassica rapa grew out of ancestral plants that lived about 6,000 years ago in Central Asia, near the Western Himalayas.

Fast Plants serve as a relevant model organism in this storyline because they, too, are classified in the genus Brassica. Wisconsin Fast Plants is the common name for a special variety of Brassica rapa. Remarkably, Brassica rapa includes many different forms of vegetables like turnips, bok choy, and broccoli rabe. Further, we now know that this group of plants called Brassica rapa grew out of ancestral plants that lived about 6,000 years ago in Central Asia, near the Western Himalayas.

Therefore, wondering about variation in these vegetables leads naturally into students planting Brassica seeds (Fast Plants) to observe closely how the plants grow and develop. Later, students use these same Fast Plants for a selective breeding experiment, because the seeds chosen have a mix of purple and non-purple stems. So, after students have learned about human selection influences on Brassicas around the world, they can implement a class breeding experiment for stem color with their Fast Plants.

The F2 Non-Purple Stem Fast Plants seed stock is used because it provides both the phenotypes and genotypes needed for students to choose either purple or non-purple stems as the “selected” trait and see quantifiable results from their selective breeding.

During the experimental design phase of this storyline, the teacher guides discussions about the goals and parameters for making selections from a population. Once the class designs a selective plant breeding experiment, those plants with the selected stem color are kept for pollination and seed production. All other plants (with the alternate stem color) are snipped out. In this way, students directly experience the goals, procedures, and outcomes of selective breeding.

During the experimental design phase of this storyline, the teacher guides discussions about the goals and parameters for making selections from a population. Once the class designs a selective plant breeding experiment, those plants with the selected stem color are kept for pollination and seed production. All other plants (with the alternate stem color) are snipped out. In this way, students directly experience the goals, procedures, and outcomes of selective breeding.

Ultimately, students cross-pollinate only those individual Fast Plants with the class-chosen stem color (purple or green stems) as a model for plant breeding. This firsthand experience with plant breeding supports learning how genetics and environmental factors influence which traits become most common in future generations.

Support for planning this selection experiment includes a customizable timeline, calendar, and planning document.

Exploring Historical Brassica Selection and Cultural Connections

Using human-guided selection (vegetable breeding) as the context for learning about variation and natural selection opens the door for connecting science with students’ lives and cultures. This is particularly true for Brassicas because they are an economically and culturally significant crop worldwide. In other words, thousands of years ago, wild Brassica ancestors were selectively bred and spread globally by humans to fulfill communities’ very different environmental conditions and cultural preferences.

Ethnobotanists’ work reveals how turnips emerged in nomadic cultures where selecting for fleshy roots provided highly portable food. Alternatively, Chinese cabbage, which shares a common ancestor with turnips, was selectively bred by other humans to form a leafy head. Most importantly, we emphasize that one Brassica isn’t superior to the other, they’re just different. Therein lies an important lesson for students about the value in genetic diversity, which makes it possible to selectively breed for traits advantageous to a particular environment and/or best suited to a community’s needs. To support learning these concepts, the Fast Plants Program of UW-Madison produced and shared online a video intended for student audiences, Brassicas Around the World and Wisconsin Fast Plants.

A 10-minute video developed by the Fast Plants Program at UW-Madison, called Brassicas Around the World and Wisconsin Fast Plants, explains what scientists understand at this time about the origins of Brassicas.

Connecting Human Selection to Natural Selection

Once you’ve guided students to a shared, robust explanation for the variation in Brassicas, applying the same ideas to understanding natural selection follows easily. In both cases, genetic and phenotypic variation must exist in the population for selection to occur. Out of this variation, we can help students relate to how some individuals are differentially selected—either by human preference or environmental advantage. Then, because selective breeding in Brassicas is such a great analogy for natural selection, the remaining tenets of natural selection become less abstract.

In addition to this storyline providing a concrete analogy for natural selection, students also learn valuable lessons about food systems. This approach offers opportunities to connect science and culture, while growing students’ understandings about the origins of crops we depend upon globally and the importance of stewarding genetic diversity.

ADDITIONAL READING

Resources

Plant breeding experiment timeline, calendar, and planning document

Brassicas Around the World and Wisconsin Fast Plants video

Scientific article about Brassica origins: “Brassica rapa Domestication: Untangling Wild and Feral Forms and Convergence of Crop Morphotypes”

Reader-friendly article about the above scientific article: “The Deep Roots of the Vegetable That ‘Took Over the World’”

*Next Generation Science Standards® is a registered trademark of WestEd. Neither WestEd nor the lead states and partners that developed the Next Generation Science Standards were involved in the production of this product, and do not endorse it.