Tardigrades

Tardigrades, also called moss piglets, (Fig. 1) are fascinating, easy to care for microscopic animals with characteristics well suited to laboratory exercises. Tardigrades (slow steppers) were named water bears by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1869 because their inherent pawing resembles the clumsy actions of circus bears. This video illustrates the tardigrade behavior Huxley likely observed. The name moss piglets was inspired by tardigrades’ pig-like snout, round body, and damp moss habitat. Their relatively large size compared to other micrometazoans makes them model organisms for brightfield and darkfield light microscopy.

Researchers estimate there are 1,000 to 1,300 species of tardigrades that comprise the phylum Tardigrada, microscopic animals living in marine, freshwater, or damp terrestrial environments throughout the world. Critters belonging to Tardigrada (part of the clade Panarthropoda, which includes arthropods, velvet worms, and crustaceans) have a main body cavity called a hemocoel with no specialized circulatory structures and a nervous system consisting of a dorsal brain connected to a ventral nerve cord with segmental ganglia. Tardigrades may share an even closer relationship with nematodes (roundworms) according to some zoologists, but this is still open to debate. Tardigrades have been found in extreme conditions, from the deep sea to polar mountain tops, and new species are still being discovered. Zoologists have evidence that these microorganisms have survived all five mass extinctions.

Tardigrade General Characteristics

Mature tardigrades range in size from 0.3 mm to over 1.2 mm in length, but most are less than 0.5 mm. Variations in size are common within a given species.

The typical tardigrade has a short, barrel-shaped body with distinct cephalization and four less well-defined body segments. A pair of legs that are short and ventrolateral extends from each body segment. Each leg has four claws or two double claws used chiefly for locomotion and clinging to plants or other substrates. Tardigrades lack cilia, although some species have cirri located anteriorly, laterally, or both.

Tardigrades are covered by a protective, proteinaceous cuticle that is secreted by the underlying epidermis. Cuticle textures range from smooth to highly sculptured and granular. The number of cells that comprise the epidermis is constant within a species and is invaluable in differentiating tardigrades taxonomically.

Tardigrade coloration varies from a bluish gray to yellow or reddish brown. Young animals are frequently transparent, especially just after emerging from an egg case, while older, mature individuals are usually dark and opaque.

Feeding

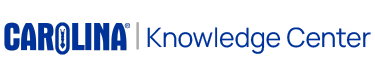

Most tardigrades feed exclusively on plants. Two long, sharp stylets located in the buccal apparatus pierce the walls of moss and algal cells and then the cells’ liquid contents are ingested by powerful pharyngeal pumping action. The video below illustrates the movement of cellular fluids within a tardigrade.

Some tardigrades occasionally consume the body fluids of small metazoans, and Milnesium tardigradum appears to be exclusively carnivorous. Contact with prey like the rotifer Philodina is apparently random, although papillae surrounding the mouth may aid in food detection. The tardigrade grasps the rotifer near its base or pedal gland, stylets puncture the cuticle, and the pharynx begins to suck the pseudocoelic fluids into its gut. The piercing action of the stylets and pharyngeal pumping are clearly visible with a light microscope at low-power magnification.

Life Cycle

Sexes are separate in most tardigrade species. Species reproduction where males are unknown is probably by parthenogenesis. The bulk of a population is composed of females; males reach their numerical peak in the winter or early spring. Most tardigrade reproduction occurs from late fall to early spring, but egg-bearing females can be observed year-round.

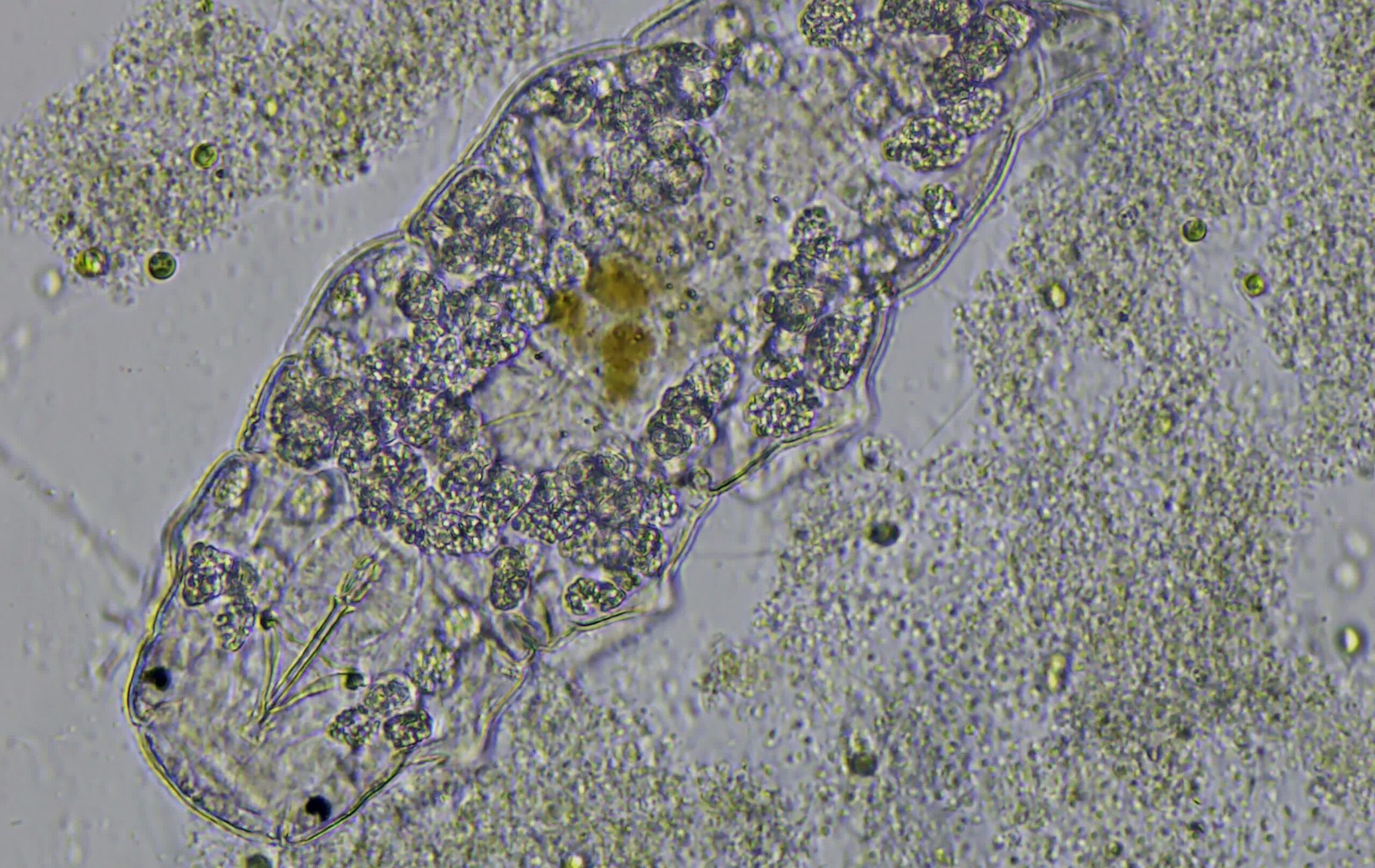

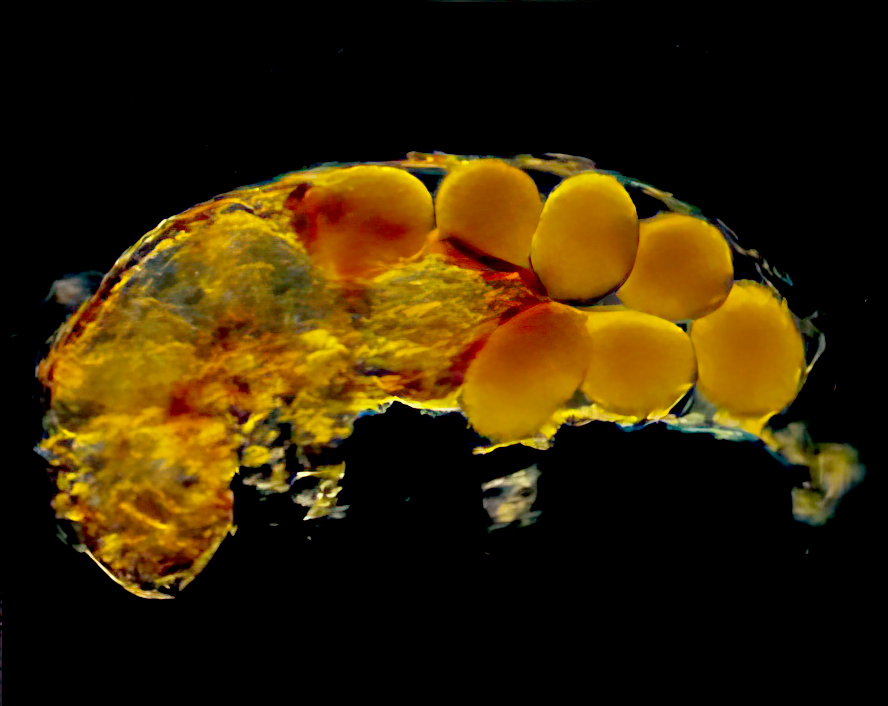

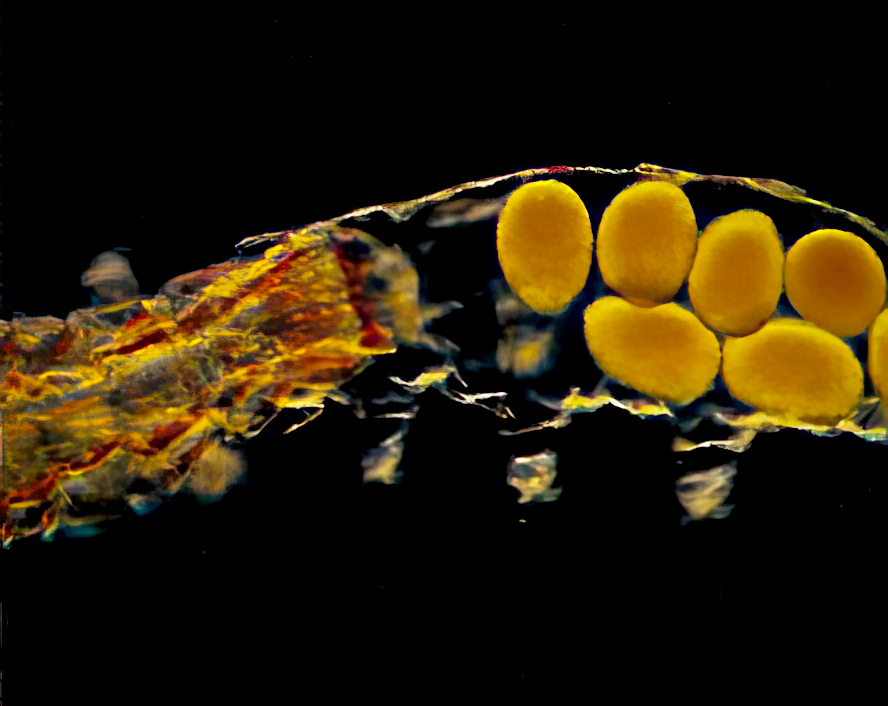

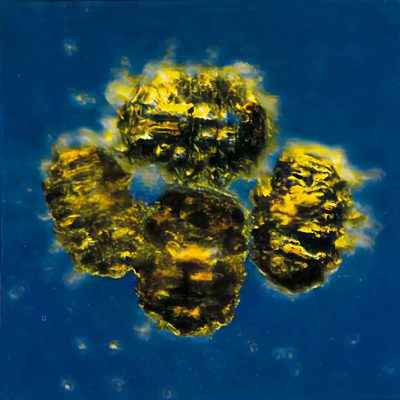

Tardigrade eggs are deposited in groups or singly, depending upon genus. Eggs may also be safely left behind in the spent cuticles (Fig. 2) as females emerge from ecdysis or molting. Eggs deposited freely are highly sculptured or have a sticky surface to aid attachment to substrates. Eggs deposited in old cuticles are usually smooth.

Two egg types, thin-shelled and thick-shelled, have been observed among several genera and may be analogous to summer and winter eggs produced by rotifers. Undoubtedly, the egg types correspond to favorable and unfavorable environmental conditions.

Embryonic developmental rate is usually dependent upon the type of egg produced. Thin-shelled eggs hatch in 3 to 12 days and thick-shelled eggs in 10 to 14 days. The young tardigrade ruptures its surrounding egg case with its stylets and emerges one-fourth to one-third adult size.

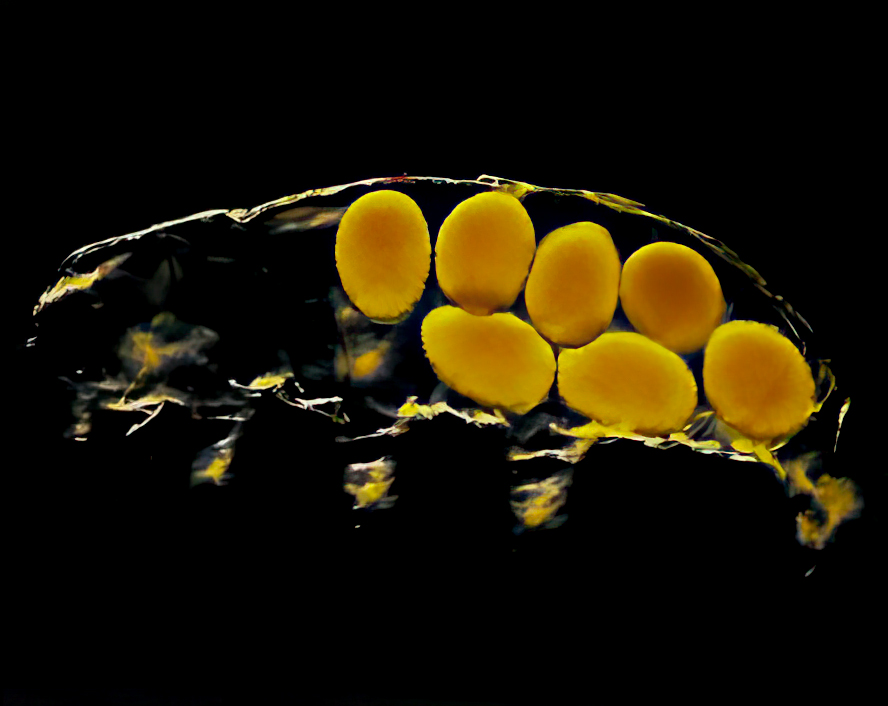

Typical tardigrades complete four to six ecdyses during a life span (Fig. 3), increasing in size until maturity after the third molt. Before ecdysis, the tardigrade shrinks slightly, becoming detached from its cuticle. The contained tardigrade then thrashes until its old cuticle ruptures. (Fig. 4). The tardigrade crawls out, leaving its old cuticle and possibly a new clutch of eggs behind (Fig. 5). The claws, mouth or buccal apparatus, and lining of the rectum are left behind as the animal exits its old cuticle. Once discarded tissues and structures are replaced, feeding resumes.

Cryptobiosis

There is considerable debate over the life span of tardigrades because of their innate cryptobiotic ability. Tardigrade research zoologists successfully designed an experiment in 2007 to expose 3,000 tardigrades to the low temperatures and vacuum of space for 10 days. Sixty-eight percent survived and successfully returned to normal conditions. In 2021, a mission on the International Space Station began studying the effects of microgravity on tardigrades.

Cryptobiotic adaptations allow water bears to withstand extreme conditions of temperature, pressure, radiation, hydration, and oxygenation. Some scientists think tardigrades in the desiccated tun state could withstand the conditions of outer space and even travel on asteroids. Researchers at UNC-Chapel Hill have sequenced the tardigrade genome and found it to contain one-sixth foreign DNA from bacteria, plants, fungi, and Archaea which may be responsible for the ability of tardigrades to survive extreme conditions.

The term cryptobiosis (hidden life) was coined by David Keilin at Cambridge University in 1959. Cryptobiosis is not limited to the phylum Tardigrada. Rotifers, nematodes, and myriad other organisms exploit cryptobiosis to endure adverse and extreme environments. Anton van Leeuwenhoek reported this phenomenon to the Royal Society of London in 1702. Cryptobiosis is now used as a collective term for a number of nonanimated states that tardigrades and other extremophiles undergo in response to varying and often extreme environmental factors.

The length of tardigrade cryptobiotic state is unknown. Dried moss specimens from a museum collection yielded tardigrades that remained desiccated for 120 years. When the animals were moistened, a number of them revived, but all died in a matter of minutes. By any standards these conditions would be considered extreme. Under natural conditions, however, cryptobiotic intervals greatly increase tardigrade longevity. Research estimates a tardigrade would only live about 18 months if it never entered cryptobiosis but could survive for over 50 years by alternating periods of animation and cryptobiosis.

Anhydrobiosis

Anhydrobiosis is probably the most common form of cryptobiosis in tardigrades. Although a few species are truly aquatic, most are semiaquatic, living in the thin surface film of moisture on lichens after a rain shower or in water droplets trapped among filaments of streamside mosses. Semiaquatic tardigrades endure fluctuation in water levels from season to season. As their surroundings begin to dry, the tardigrade undergoes a remarkable adaptive procedure. The head, posterior end, and legs of the desiccating animal contract to form a rounded tun state. (Fig. 6). A large fraction (research estimates as much as 97%) of water content is lost entering anhydrobiosis.

Cellular membrane damage and irrevocable damage to three-dimensional structures of many larger organic molecules resulting in death would be expected. However, electron micrographs of cryptobiotic and active tardigrades suggest the formation of a tun involves a tight and orderly packaging of cellular systems and components, limiting gross mechanical damage from dehydration. The shape of a tun also aids in lowering water evaporation rate. Body surfaces that would normally be moisture-permeable are withdrawn from air contact, lowering the rate of water loss a thousandfold.

For successful revival from anhydrobiosis, water loss must occur at a slow and controlled rate. In laboratory experiments, all animals that were quickly dried perished. Evidently some physiological state must be achieved prior to complete desiccation to insure return from anhydrobiosis.

According to biologist James Clegg, a leader in cryptobiotic research, a tardigrade produces two compounds not normally associated with active animals as it begins to dry. Trehalose, a sugar with two glucose molecules incorporated within its structure, and glycerol must be synthesized in sufficient quantities if the animal is to revive. These two compounds may form an internal matrix that preserves the integrity of the cellular membranes and the three-dimensional structures of the large organic molecules.

As favorable conditions return and water is abundant, tissues inside the tun begin to swell. The trehalose and glycerol molecules are returned to solution, allowing molecules to assume normal structures and chemical reactions. The once-desiccated animal springs back to life. The newly revived animal does not awaken hungry either, for the trehalose and glycerol can be metabolized for energy until normal feeding and digestion begin.

Anoxybiosis

Another similar cryptobiotic state, anoxybiosis, occurs when tardigrades are subjected to low oxygen levels. The tardigrade body swells, becoming turgid and distended. There is no movement, and life is difficult to discern. Death occurs within five days unless oxygen supplies are replenished. If oxygen is supplied at required levels, the formerly turgid animal resumes its normal body morphology and activities.

Tardigrade Laboratory Demonstrations

Anhydrobiosis and anoxybiosis are easily induced in laboratory experiments. To induce anhydrobiosis, add a few milliliters of distilled water to a culture dish containing active tardigrades and then allow the water to evaporate at room temperature. If the resulting tuns are carefully and gently placed in the well of a concavity slide along with a drop of water, the revival process can be observed with a stereomicroscope.

Anoxybiosis can be induced by covering a culture dish containing active tardigrades to prevent gas exchange. In a matter of hours swollen and motionless individuals can be observed lying on the bottom of the dish. To revive the apparently lifeless animals, decant most of the water from the dish and replace it with vigorously agitated distilled water or springwater. (Tap water may contain ions lethal to many protozoans or micrometazoans.) Soon the anoxybiotic tardigrades will resume their normal activities.

Tardigrades are intriguing, easy to care for animals that make ideal choices for studies of life science, cryptobiosis, and other topics. Their uniqueness reflects a very specialized and highly adaptive way of life that continues to baffle and entertain those who study them.

This article was originally published as “Water Bears” in Carolina Tips®, Vol. 49, No. 1 (print version, January 1986); it was revised November 2025.

Further Reading

Barth, R. H. and Broshears, R. E., The Invertebrate World, Saunders College Publishing, Philadelphia, 1982.

Boothby, T. and Goldstein, B., “Large percentage of a tardigrade’s genome comes from foreign DNA,” Carolina News and Notes, Chapel Hill, NC, https://magazine.college.unc.edu/college-news-notes/tardigrades/, accessed October 2025.

Pennak, R. W., Fresh-Water Invertebrates of the United States, 2nd edition, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1978.

Zaitsev, A. S., Gongalsky, K. B., Nakamori, T., Kaneko, N., “Ionizing radiation effects on soil biota: Application of lessons learned from Chernobyl accident for radiological monitoring,” https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2013.09.005, accessed October 2025.

David E. King

From the Cultures Department

About The Author

Carolina Staff

Carolina is teamed with teachers and continually provides valuable resources–articles, activities, and how-to videos–to help teachers in their classroom.