As early as 1000 BCE, domestic fowls were common in India. They were probably derived from the wild cock of the Indian bamboo jungles. Domesticated chickens were also established early in China. From these centers, they spread throughout Asia, Europe, and Africa. Christopher Columbus brought chickens on his second voyage to the New World. The Jamestown colonists, like generations of homesteaders and farmers before and after them, were awakened to their daily chores by the cock’s crow.

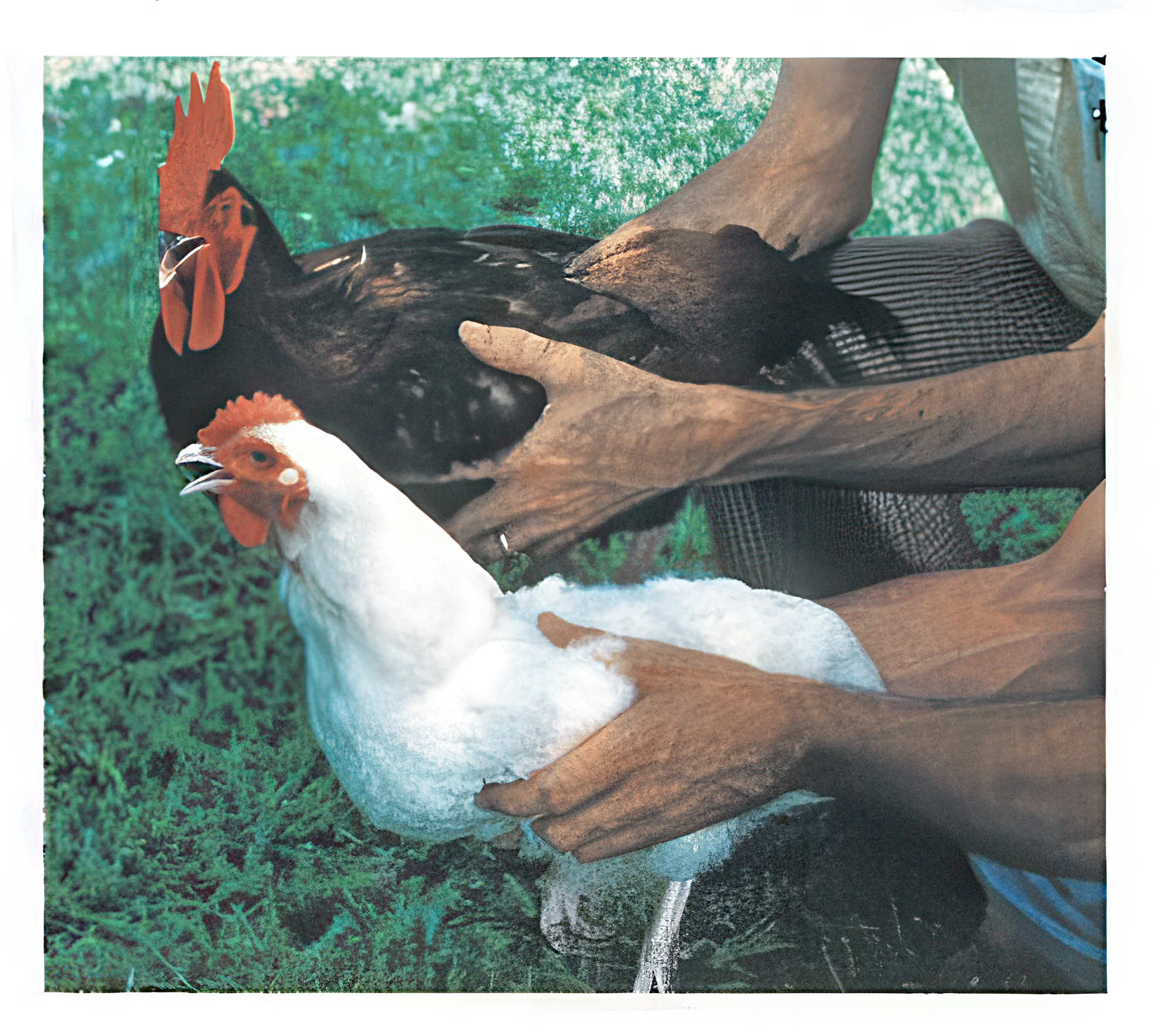

From the time of Jamestown until the late 1940s, most households in rural America kept a small flock of chickens for eggs, meat, and amusement. One presidential candidate even used the slogan “a chicken in every pot” as a promise of better times ahead. Small family flocks (Fig. 1) diminished rapidly when it became a simple matter to pick up a dozen eggs and a fryer at the supermarket. Rising egg prices in the 21st century have led to a resurgence of backyard chickens.

Egg Formation

Chickens mature quickly. Under good conditions, a hen will begin to lay eggs soon after her twenty-first week. An egg begins as an oocyte in the ovary (Fig. 2). The oocyte is covered by a membrane and develops a yolk as it ripens; the entire structure is a follicle. Ovulation is stimulated by the release of a pituitary hormone.

Upon release, the oocyte is usually grasped by the infundibulum and moves into the left oviduct, where the final stages in egg formation occur. (The right ovary and oviduct are vestigial or absent.) As the mature oocyte passes down the magnum, albumen is added to it, forming the egg white. The two shell membranes are secreted around the egg as it passes through the isthmus. The egg then enters the uterus or shell gland. Within the uterus, water and salts are added to the egg, increasing its size.

A shell of calcite, a crystalline form of calcium carbonate, is formed around the egg. A cuticle is then added to the shell, and the egg is laid. Because of the timing of these various events, egg-laying usually occurs in the afternoon.

Development and Chick Hatching

From the consumer’s standpoint, the chicken egg is a conveniently prepackaged food. Biologically, it is a method of reproducing the chicken. The egg can develop into a chick only if it has been fertilized by a rooster, an event that must occur soon after the mature oocyte enters the infundibulum.

The fertile egg (Fig. 3) also needs incubation for embryonic development. Today, incubation is usually accomplished artificially with an incubator. When using an incubator, it is important to provide proper humidity; otherwise, the egg may lose water by evaporation until the embryo dies. It is also important to turn the eggs at least daily, or the embryonic membranes may adhere to the shell, resulting in damaged chicks.

If left to her own instincts, the hen will probably begin incubating the eggs when 6 to 10 eggs have accumulated in her nest. At this time, the hen exhibits brooding behavior. Her feathers are fluffed, her head is held close to her body, and she occasionally emits short, harsh clucks. Anthropomorphically speaking, she appears grumpy. She stops laying and spends most of her time sitting on the eggs. Broodiness is a disadvantage for the egg farmer because it takes hens out of egg production. The tendency toward broodiness is inherited in chickens, and most varieties have had the trait bred out, so they seldom become broody.

In the initial stages of chick development, cleavage does not proceed through the yolk mass; it is limited to a disc-shaped area of protoplasm on the yolk surface. Continued cleavage produces a blastula. Gastrulation occurs by the migration of cells inward along an area on the edge of the blastula, creating a thickening, the primitive streak (Fig. 4). The primitive streak is thought to represent the elongated, fused lips of the blastopore.

![FIGURE 3 Diagrammatic section through a fertile egg.]](https://knowledge.carolina.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/1981_February_Fig_03-scaled.jpg)

A fold (the neural fold, Fig. 5) eventually develops in the ectodermal tissue anterior to the primitive streak as the streak regresses. The neural fold then fuses along its dorsal surface to form a tube. The anterior end of the tube becomes the embryonic brain, and the posterior portion gives rise to the spinal cord and nerves other than the cranial nerves. Mesoderm parallel to the neural fold gives rise to lateral somites (Fig. 6), segmented blocks of muscle. (Development of the embryo proceeds more rapidly toward the anterior end.) Slightly later, blood vessels develop from mesoderm ventral to the nervous system; portions of these vessels then enlarge and differentiate to become the heart (Fig. 7). These and later stages of chick embryo development are easily observed (Fig. 8, 9, 10, 11).

At the end of the incubation period (about 21 days), the fully developed chick cuts through (pips) the eggshell with its egg tooth (Fig. 12). The egg tooth is a temporary horny protuberance on the upper mandible. A special hatching muscle aids in cutting through the shell. In pipping the eggshell, the chick’s body jerks, forcing the beak against the shell. In this manner, the egg tooth cuts through the shell membranes and eventually the shell itself (Fig. 13).

The shell is cut approximately around the circumference of its short axis (Fig. 14), and the newly hatched chick, wet and exhausted from the effort, emerges (Fig. 15, 16, 17). Soon, its feathers dry, and the chick can run about. Yolk reserves within the body nourish the chick for two or three days; through random pecking, the chick usually discovers food and water. As the chick matures, the down feathers are replaced by adult feathers. The young hens are referred to as pullets, while the young males are referred to as cockerels.

Adulthood

Each adult chicken soon becomes established in the pecking order of the flock. This is actually a dominance hierarchy, of which pecking is the most visible aspect. If both males and females are present in the flock, two pecking orders develop, one for the roosters and one for the adult hens. The most dominant hen can peck all other hens without reprisal; the second most dominant hen can peck all other hens except the most dominant, and so forth. This continues on down to one poor hen that gets pecked by all.

Once the peck order is well established, actual pecking declines as subordinate hens learn to give way to dominant hens. Eventually, dominance or submission may be indicated by a simple raising or lowering of the head. The higher-ranking hens have the best access to food and water, and the first choice of roosting places and nests.

The peck order of roosters is similar to that of hens, but because the cocks are more aggressive, actual fights may occur. Two cocks stand facing each other with heads lowered and neck feathers ruffled. Suddenly, they spring forward and upward, flapping their wings and striking at each other with the long spurs on their legs. This continues until one cock turns away or runs. A low-ranking cock that attempts to mate with a hen will often be chased away by a high-ranking cock.

If allowed to range, chickens will eat small animals (earthworms, grubs, caterpillars, adult insects, etc.) in addition to the seeds and shoots of various plants. The chicken searches about, pecking here and there for food and occasionally scratching the ground alternately with its feet.

Once swallowed, the food does not immediately enter the stomach but goes to the crop for storage. From the crop, the food eventually enters the gizzard, a thick-walled organ that grinds the food with grit by muscular contractions. Chickens swallow grit for this purpose. The grit also provides calcium for skeletal development. This is especially important to the hen because she mobilizes skeletal calcium to form eggshells, and without calcium she will lay few eggs.

Under natural conditions, the hens begin egg-laying in late winter as the days lengthen. Roosters are needed only if fertile eggs are desired. A healthy barnyard hen will lay about 200 eggs a year. If kept in a lighted, heated building with abundant food, she might approach laying an egg a day.

Breeders try to keep about one rooster for every 12 hens to ensure fertile eggs. In mating, the rooster mounts the squatting hen and crouches on her back. He rubs his vent against hers and the sperm travels up the hen’s oviduct. The sperm remains viable for several days, and at a sex ratio of 1 cock to 12 hens, a hen will be mated at least every two or three days. Thus, all the eggs are likely to be fertile. As long as the eggs are removed from the nest, the hen will continue laying eggs. If six or more eggs are allowed to accumulate, the hen may become broody.

When not feeding or mating, chickens may preen or take dust baths. In preening, the chicken rubs oil from an oil gland onto its beak and strokes its feathers, coating them with the oil. This waterproofs the feathers, keeps them from becoming brittle, and gives the plumage a healthy appearance. Dust bathing consists of crouching or sprawling in dry dust, dirt, or ashes and repeatedly fluffing the feathers. Dust bathing and preening are usually signs of good health.

Genetics

Artificial selection has produced many breeds of chickens along the lines of fighting, show or novelty, egg production, and meat production. The characteristics selected usually involve egg-laying ability, color, and the structure or shape of the body or body parts, such as the comb. Today, breeders are trying to develop disease resistance, docility, good egg size, quality, and faster growth and maturity into chicken breeds. The result for the teaching biologist is a wealth of genetic material for instructional use.

Some of the most interesting aspects of inheritance in chickens involves sex related inheritance. In humans, the male is XY and the female is XX. This situation is essentially reversed in chickens and many other birds. The male chicken is ZZ and the female is ZW. (The designations Z and W rather than X and Y are used to avoid confusion between the two methods of sex determination.) Thus, in humans, a recessive sex-linked gene such as red-green color blindness can be transmitted by the female and expressed in her male offspring, but not in her daughters if the father has normal color vision.

The opposite pattern can be demonstrated in chickens. The barred/nonbarred cross in Plymouth Rocks is a good example. Figure 18 shows the parent stock of such a cross. The male is nonbarred (b/b), the female is barred (B/W). Upon hatching, the male offspring (B/b) has a light spot on the top of his head while the female (b/W) does not (Fig. 19). In adult plumage, the male is barred and the female nonbarred. In other words, the male parent’s recessive gene is expressed in his female offspring but not in his male offspring. Several similar examples, such as red/white crosses, are known (Fig. 20, 21).

Chickens also provide a good demonstration of sex-limited inheritance. Sex-limited genes are often confused with sex-linked genes, but the inheritance pattern is completely different. Sex-linked genes are carried on the sex chromosomes. Sex-limited genes are carried on the autosomes but are usually expressed in only one of the sexes. The beard is an example of a sex-limited trait in humans.

Male Leghorns have long, curved, pointed feathers on the neck and tail, while female Leghorns have shorter, straighter, more rounded neck and tail feathers. This is termed cock and hen feathering, respectively. In the Sebright bantam, both male and female are hen-feathered. But in the Hamburg breed, males may be either cock-feathered or hen-feathered while females are always hen-feathered. This is explained by the operation of gene H, which produces hen feathering, and its allele h, which produces cock feathering in males only. Thus, Leghorns are h/h and Sebright bantams are H/H. In Hamburgs, H/H or H/h chickens are hen-feathered whether male or female, but all h/h females are hen-feathered while all h/h males are cock-feathered. The expression of allele h is limited to one sex.

If the ovaries or testes are removed and the chickens are allowed to molt, they will become cock-feathered, regardless of genotype. Thus, we see that the action of these genes is dependent upon the presence or absence of the sex hormones.

This article was originally published as “The Domestic Chicken” in Carolina Tips®, Vol. 44, No. 2 (print version, February 1981); it was revised July 2025.

Related Products

The life cycle of chickens provides excellent learning opportunities for all ages and abilities. Observing egg hatching is a great alternative in elementary grades to other life cycle activities, such as observing the frog life cycle or observing the life cycles of butterflies. Chicken dissection can be a valuable activity for comparative anatomy or in an agricultural science course. Whatever your learning objectives, Carolina has the products you need.

Beginner's Chick Whole Mount Microscope Slide Set

Various stages of chick development are represented in this set of 5 slides.

Chick Embryology Microscope Slide Set

A set of 12 slides demonstrating chick development. Includes whole mounts, serial sections, and representative sections of varying ages.

General Embryology Microscope Slide Set

A set of 25 slides designed for vertebrate embryology with special emphasis on the chick.

Formalin Preserved Chickens

Explore avian anatomy with the preserved chicken.

Chicken Skeleton, Articulated

Natural bone. Large, with eye rings and hyoid bones.

Altay® Hen Model

Altay®. Life size. This 8-part model depicts hen anatomy in great detail.

Incubator, Sportsman

This complete incubator and hatcher now offers an accurate digital thermostat with LCD display of temperature and humidity, as well as electronic egg turning, audio/visual alarms, and a standard easy-view door.

Digital Still-Air Incubator with Automatic Turner

Engage your students in a science activity they will remember their entire lives—hatching chickens!

Brooder Lamp with Bulb

Provide warmth to newly hatched chickens, ducks, or quail with a basic brooder lamp.

Mini Advance Incubator

Get an excellent view of eggs during incubation and hatching with this incubator's clear plastic dome.

Recessive White Chicken DNA Test, 38 Tests

See how many copies of the recessive white allele your chicken is carrying!

Blue Egg Gene (oocyan allele [O]) Chicken DNA Test, 38 Tests

See how many copies of the blue egg gene your chicken is carrying!

Related Content

The life cycle of chickens provides excellent learning opportunities for all ages and abilities. Observing egg hatching is a great alternative in elementary grades to other life cycle activities, such as observing the frog life cycle or observing the life cycles of butterflies. Chicken dissection can be a valuable activity for comparative anatomy or in an agricultural science course. Whatever your learning objectives, Carolina has the products you need.

Chicken Wing Musculature

Explore the structures and functions of muscle tissue Essential Question...

Read MoreFurther Reading

Jull, Morley A. 1936. “Superior Breeding Stock in Poultry.” In Yearbook of Agriculture: 1936, 947-995. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Rugh, Roberts. 1948. Experimental Embryology: A Manual of Techniques and Procedures. Minneapolis: Burgess Publishing Company.

Taylor, T. G. 1970. “How an Eggshell Is Made.” Scientific American 222, no. 3 (March): 88-97.

About The Author

Carolina Staff

Carolina is teamed with teachers and continually provides valuable resources–articles, activities, and how-to videos–to help teachers in their classroom.